Civil War History

Your Guide to Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley

Civil War Sites Battlefields, Museums,

Historic Homes, and More!

The Bed and Breakfasts of the Historic Shenandoah Valley have provided you with this guide as a reminder of the importance of the Shenandoah Valley as not only a food provider during the Civil War but as an important strategic location for the Southern Armies of General Robert E. Lee as his link to the North. As you will discover, there were many Virginia Civil War battles and many heroes made and broken in the Shenandoah Valley.

Upon visiting “The Valley” and looking at the terrain that was traversed on a daily basis, you will begin to understand the tenacity of the soldiers that fought in this war.

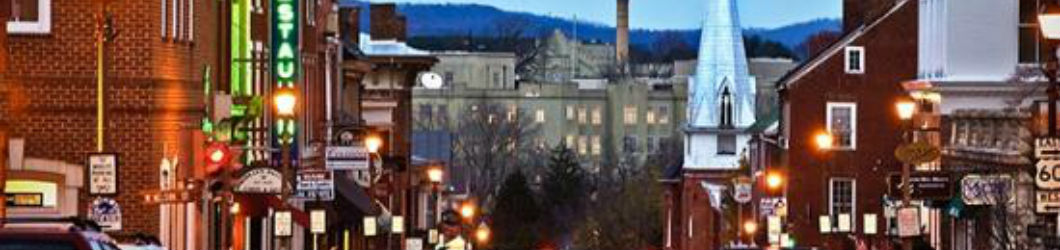

You will discover that the original North-South road, Route 11, is still a very active highway running through and connecting many of the towns in the Shenandoah Valley, from the north of Winchester to south of Lexington. These towns and their residents are what make the Shenandoah Valley a wonderful place to visit. You will discover the hospitality of the people of this region that makes it what it is today.

The Civil War in the Shenandoah Valley:

A Brief History

During the Civil War, the Shenandoah Valley was one of the most hotly contested areas in the north or the south. The Valley was Virginia’s breadbasket, providing provisions for the large armies that operated there. It also was a key route to the Confederate capital of Richmond, forming a natural corridor through which Union armies could penetrate deep into Virginia and threaten the city from the rear. Military historians remember the Valley as the site of one of the greatest campaigns in the history of warfare, Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s spring campaign of 1862. The Shenandoah Valley was continually conquered and re-conquered during the war and is one of the few regions that can be said to have had a great impact on both sides for the duration of the hostilities.

On May 24, 1861, the day after Virginia’s citizens voted in favor of secession from the Union, a Federal force occupied Alexandria, effectively controlling the whole of northern Virginia. Union soldiers would occupy the area for virtually the entire war. This bloodless loss for the Confederates ultimately meant that the Shenandoah Valley would be relied upon more and more to sustain the armies of the south and that its protection from invasion was of the utmost importance.

Although important from the beginning agriculturally, the Shenandoah Valley did not figure prominently in terms of engagements and campaigning until Jackson’s daring marches, train rides, and pitched battles beginning in the early spring of 1862. At this point, General George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac had traveled by boat up the James River and was sitting on the doorstep of Richmond, facing a Confederate force under Joseph Johnston that was severely outnumbered. McClellan, however, stopped in his tracks at the first hint of resistance and demanded that additional troops be provided to him. The men he requested were stationed in Fredericksburg, under the command of Irwin McDowell, and numbered over 40,000. Jackson’s goal was to make Union commanders, most notably the cautious President Lincoln, believe that he could threaten Washington, D.C., thereby forcing them to keep McDowell at Fredericksburg where he could be easily relocated if the defense of Washington became necessary. This was a fairly lofty goal to be accomplished with Jackson’s starting force of less than 3,000 men.

Jackson began his campaign by attacking a much larger Union force at Kernstown, just south of Winchester. The battle was never intended to be a tactical victory. The Confederate attack was easily repulsed, but Jackson had correctly assumed that Lincoln would overreact to his ploy, keeping McDowell in Fredericksburg and canceling plans to dispatch a detachment of Nathaniel Banks’ army, then at Harper’s Ferry, to assist McClellan. Jackson also hoped to represent a stronger force than he actually commanded, and in this, too, he succeeded.

Jackson continued to build his forces, elude two Federal armies, pull out of the Valley entirely in order to further confuse his enemy, and win decisive victories at Winchester and Port Republic. His campaign was a stunning success, removing the threat to the Valley, occupying some 78,000 Union soldiers, and giving Confederate armies around Richmond the time they needed to adequately defend the capital, all with a force that, at its strongest, numbered no more than 17,000. It is not an embellishment to say that Jackson’s actions in the Shenandoah Valley prolonged the War by almost three years.

During Robert E. Lee’s Gettysburg campaign in the summer of 1863, the Valley was used as the main avenue of the southern advance into Maryland and Pennsylvania, using the Blue Ridge Mountains to screen his army’s movements. Winchester, Strasburg, and New Market also provided countless new recruits for the drive north. Lee defeated a sizable Federal garrison at Winchester on June 15, clearing the path into Union territory, and allowing his Army of Northern Virginia to continue on to the fateful Battle of Gettysburg. After Lee was defeated at Gettysburg, he again used the Valley to march his troops back toward the Confederate capital.

The final major campaign in the Shenandoah Valley occurred from the spring through the fall of 1864 and was characterized by several fierce battles and the destruction of much of the agricultural value of the area by the cavalry of Philip Sheridan. The campaign began when Franz Sigel’s Federal army was ordered to capture the Valley as far south as Harrisonburg in order to prevent the rebel forces there from becoming a nuisance as U.S. Grant led the Army of the Potomac in a final drive toward Richmond. Sigel was driven back at New Market and forced to vacate the Valley.

The Federals soon returned and were again beaten back by Jubal Early’s Confederates, this time at Kernstown. However, Union reinforcements soon arrived, and Early’s army was overpowered at the Third Battle of Winchester, forcing his retreat out of the Valley and leaving it at the mercy of Sheridan’s newly-arrived cavalry forces. Sheridan was ordered to destroy the Valley’s ability to sustain troops and demoralize its citizens, which he did promptly and violently, tearing up railroad tracks and setting fire to barns and mills.

The final battle of the Shenandoah Valley occurred at Cedar Creek on October 9, 1864, where Early’s initially successful attacks were soon thrown back and the Confederate army was routed, giving the Federals free reign of the Valley. The Civil War ended several months later when Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox.

Civil War Memories – Stories and Songs

The articles and books below were written by soldiers and citizens who actually lived through the Civil War in Virginia. They provide an interesting perspective of what happened during the war and how life changed after the war.

The Valley Campaigns:

- Being the Reminiscences of a Non-Combatant While Between the Lines in the Shenandoah Valley During the War of the States (This is about life in Front Royal, Virginia, an excellent read to get a real feel of life in the Northern Shenandoah Valley and events during the Civil War)

- How a One-Legged Rebel Lives: Reminiscences of the Civil War

- A Condensed Anti-Slavery Bible Argument; By a Citizen of Virginia

- The Memoirs of Colonel John S. Mosby

- A Soldier’s Recollections: Leaves From The Diary of a Young Confederate

- Robert E. Lee Papers at the Special Collections Department of the James Graham Leyburn Library at Washington and Lee University

- Lieutenant General Jubal Anderson Early C.S.A. – Autobiographical Sketch and Narrative of the War Between the States

- Sheridans “Early” Victory